The many facets of the Dunning-Kruger effect

It was 1999 when social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger decided to conduct a little experiment. Of course, a ‘little experiment’ doesn’t win a Nobel Prize; this experiment was conducted several times over, and the findings confirmed something we had suspected for thousands of years. The study revealed that people lacking knowledge in a particular area often overestimated their knowledge and ability. The study, known as Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognising One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments, has gained esteem and become widely referenced outside of psychology. What exactly did they learn, and how does this affliction affect our lives?

The Dunning-Kruger study

Using their students as test subjects, David Dunning and Justin Kruger sought to better understand how we perceive our performance in relation to how we actually perform. They asked their students how well they thought they performed in their tests and assignments and compared their answers to their actual scores. The experiment was conducted across subjects of grammar, logic, and humour. For added measure, the psychology duo later conducted the same test over other areas of knowledge, including business, politics, and medicine. The results were consistent. Poor performers overestimated their ability, and high performers underestimated theirs. This was by no means a revelation; this theory had been pondered by philosophers and like-minded intellectuals since what may feel like the beginning of time.

Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.

Confucius ((551–479 BC)

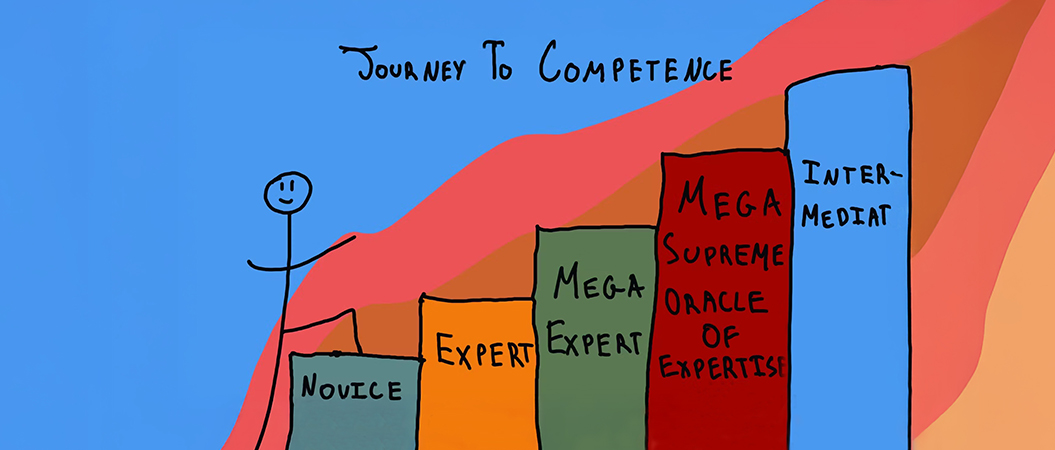

This cognitive bias, whereby students overestimated their ability, is best understood as simply not knowing enough about a topic to understand how much you don’t know. The middle of the road students were more aware that they had yet to master the subject, while those in the top quarter percentile tended to underestimate themselves. Dunning and Kruger referred to the instances in which top performers underestimated their skills as the double curse. In more extreme cases, it has become known as the imposter syndrome, whereby one grossly underestimates their abilities and thus sees themselves as an imposter amongst their peers.

The real-world effects of the Dunning-Kruger cognitive bias Through the Dunning-Kruger study, we have come to see that the more you know, the more you realise you don’t know. Unfortunately, the less you know, the less likely you are to know what it is that you don’t know. Such cognitive bias on either end of the spectrum has real-world implications. Those who are too self-assured win the popular vote through unearned confidence. Those who are highly skilled underestimate themselves, and as a result, they tend to assume that others are equally capable, possibly an even more grave mistake.

Those caught in a bubble of illusory superiority are often spotted at the end of a dining room table at a family dinner, proclaiming a deep knowledge of that with which they are most impassioned. Unfortunately, in some instances, these same people may not be willing to give way to alternate opinions. Assuming that no one else knows as much on the topic, a fair and even discussion may be lost to a monologue. In one’s personal life, this manifestation of the Dunning-Kruger effect will undoubtedly alienate those nearest and dearest. In work settings, the consequences for being caught out may be more dire.

Those on the opposite end of the spectrum, those with more profound, hard-won knowledge, will likely assume that everyone else is on the same page or even simply dismiss those who are misinformed. In this instance, everyone loses. When the opportunity arises for a more nuanced conversation with someone who is most enthused on a topic, it gives way to the transfer of knowledge. It is up to those who are highly knowledgeable to ‘suffer the fool’ insofar as there can be a balanced discussion. If the less informed individual is willing to listen, they may be inspired to pursue this field of knowledge further. Alternatively, those unwilling to offer equal airtime to others may never broaden the bounds of their knowledge.

How to combat the Dunning-Kruger effect

If you’ve had a giggle at ‘the fool’, now is the time for a truth bomb. Each one of us may fall on the less complimentary end of the Dunning-Kruger spectrum. It is not only the big talking middle manager, the awkward family member, or the friendof- a-friend which no one likes; it could also be you. Everyone has walked out of an exam marvelling at their performance only to be greeted with a vastly different mark to what was expected – if not, then bully for you. The mortals amongst us may read a book or take a short course and become obsessed with this sliver of knowledge, but does an inaccurate selfperception cloud it?

For those more open to introspection and self-awareness, the first step is admitting you may have a problem. If you’re still unsure, there’s no harm in exploring the thought further. There are ways to mitigate the risk of becoming your own acolyte, and they involve looking outwards. This affliction may be easier to tackle in a work setting. Start by asking for feedback and seriously considering what you hear. It is easy to dismiss the opinions of others, but be open to what they have to say. Take this feedback, track your performance from one day to the next, focusing on specific tasks to see your improvements. Another helpful way to combat the Dunning-Kruger effect is to seek out a qualified mentor, not a peer, but a professional with credentials who can offer more formal instruction to accelerate your learning. By taking the initiative to address your misconceptions, you remove the barriers to new knowledge.

The 1999 study conducted by David Dunning and Justin Kruger won the Ig Nobel Prize in 2000. This award is dedicated to achievements that initially make people laugh, but then make them think. The greatest lesson we can glean from this study is to be humble and cautious in our opinions.