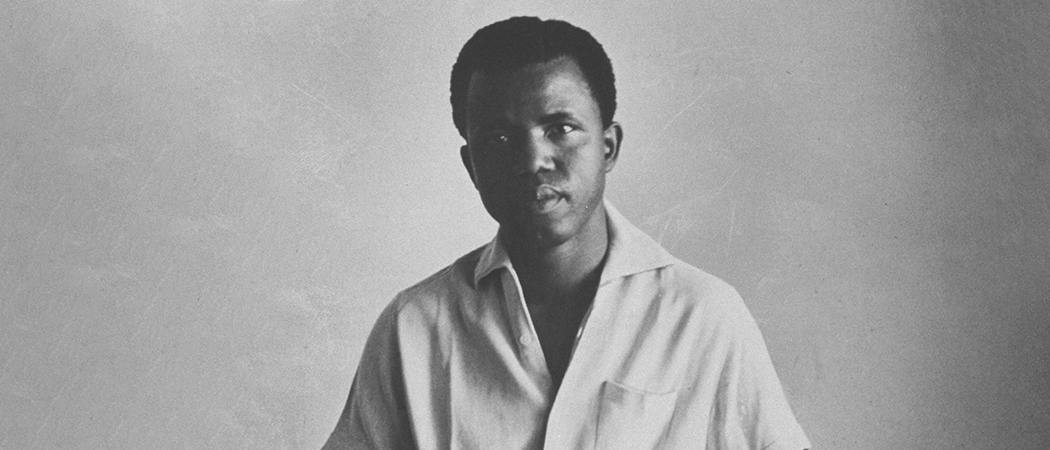

Nigeria’s national treasure

Biography: Chinua Achebe

He may have famously stated: “If you don’t like my story, write your own”, but Chinua Achebe certainly never lacked an audience and was instrumental in placing a spotlight on African literature.

Chinua Achebe is probably best known for his first novel Things Fall Apart, which is considered his masterpiece by many and the most widely read and relevant book in modern African literature. By the time of his death he had penned more than 20 works – a collection that included novels, short stories, essays and poetry.

It seems Achebe was always destined for literary greatness, already showing great promise as a young scholar. Born Albert Chinualumogu Achebe on 16 November 1930 to Isaiah and Janet Achebe in Ogidi, an Igbo village in eastern Nigeria where his father was a teacher at a missionary school, he was good student. He was learning English from the age of eight, was chosen to attend Government College in Umuahia, a secondary school which had a strict selection policy, at age 14 and was awarded a scholarship to study medicine at University College in lbadan. After a year, however, he forfeited his scholarship when he hung up his stethoscope in favour of English literature, history and theology, accepting financial support from his older brother. It was also at this time that he chose to be known by his indigenous name Chinua rather than Albert.

After graduating in 1953, Achebe travelled and worked for a short while as a teacher in America. It was here that he became aware of the lack of exposure both to Africa’s challenges and to the continent’s writing, and what he believed to be inaccurate portrayals by non-African writers.

When Achebe returned to Nigeria in 1954 he took up a position at the Nigerian Broadcasting Company and four years later, in 1958, he wrote his first novel, Things Fall Apart. The novel centres around life in Igbo, where Achebe grew up. The main character is Okonkwo, a young man whose ambition is all about being anything but what his father wants. After accidentally killing a clansman, he is banished from his community, only returning from exile seven years later. On his return he cannot accept how Western customs and values have impacted his culture and how his community is changing. Slowly for him things fall apart. One of the key themes is that of change versus tradition, and how this tension affects the characters.

Achebe was particularly productive in the 60s. He married Christie Chinwe Okoli in 1961 and produced four children and three more novels - No Longer at Ease (1960), Arrow of God (1964) and A Man of the People (1966). All are set in Africa and describe the Africans’ struggle to free themselves from European political influences. He openly supported the Nigerian civil war for Biafran independence (1967-1970) and this influenced his writings further. In 1967 Achebe co-founded Citadel Press with poet Christopher Okigbo in an effort to provide an outlet for African-oriented children’s books. Unfortunately, not long after, Okigbo was killed in the civil war.

By now Achebe was a visible public figure and a key voice in both politics and culture, which led to him touring the US with fellow writers Gabriel Okara and Cyprian Ekwensi to raise awareness of the conflict in his home country. He lectured during this time and also served in faculty positions at the University of Massachusetts and the University of Connecticut. On his return to Nigeria he was appointed research fellow at the University of Nigeria and held the position of professor of English from 1976 to 1981 and Professor Emeritus from 1985. He also served as director of two Nigerian publishers from 1970 and helped found the literary magazine Okike in 1971.

Twenty years after his last novel he released Anthills of the Savannah in 1987, which was shortlisted for the Booker McConnell Prize, followed swiftly by an essay collection titled Hopes and Impediments a year later.

Sadly the 1990s got off to a tragic start. In March 1990, Achebe, his son and driver were involved in a car accident in Lagos. While the other two sustained minor injuries, Achebe’s spine was severely damaged, leaving him paralysed and confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. He underwent treatment in England and then moved to the United States where he ardently continued his work, despite the setback.

After a 15 year stint as the Charles P. Stevenson Professor of Languages and Literature at Bard College near New York City, he joined Bron University in Rhode Island, as the David and Marianna Fisher University Professor and Professor of Africana Studies.

When Achebe died after a short illness on March 21, 2013 at the age of 82, he was living in Boston, Massachusetts. His accolades included the Man Booker International Prize (2007), the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize (2010) and honorary degrees from more than 30 universities around the world. Things Fall Apart has sold more than 20 million copies and been translated into more than 50 languages.

Words of wisdom

Achebe expressed so many memorable quotes that combine humour and warmth with Igbo proverbs. As he so eloquently explained, “Among the Igbo the art of conversation is regarded very highly, and proverbs are the palm oil with which words are eaten.” If more people heeded his words below, the world would be a much calmer and more forgiving place.

- One of the truest tests of integrity is its blunt refusal to be compromised.

- We cannot trample upon the humanity of others without devaluing our own. The Igbo put it concretely in their proverb: “He who will hold another down in the mud must stay in the mud to keep him down.”

- The only thing we have learnt from experience is that we learn nothing from experience.

- When suffering knocks at your door and you say there is no seat for him, he tells you not to worry because he has brought his own stool.

- A man who makes trouble for others is also making trouble for himself.

- While we do our good works let us not forget that the real solution lies in a world in which charity will have become unnecessary.

When old people speak it is not because of the sweetness of words in our mouths; it is because we see something which you do not see.