Guernica revisited – the resonance of Picasso’s masterpiece in today’s world

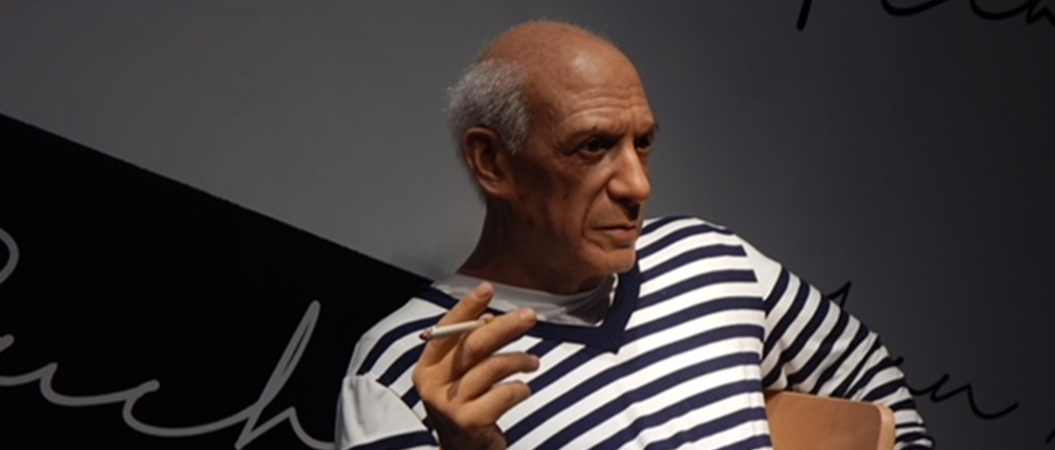

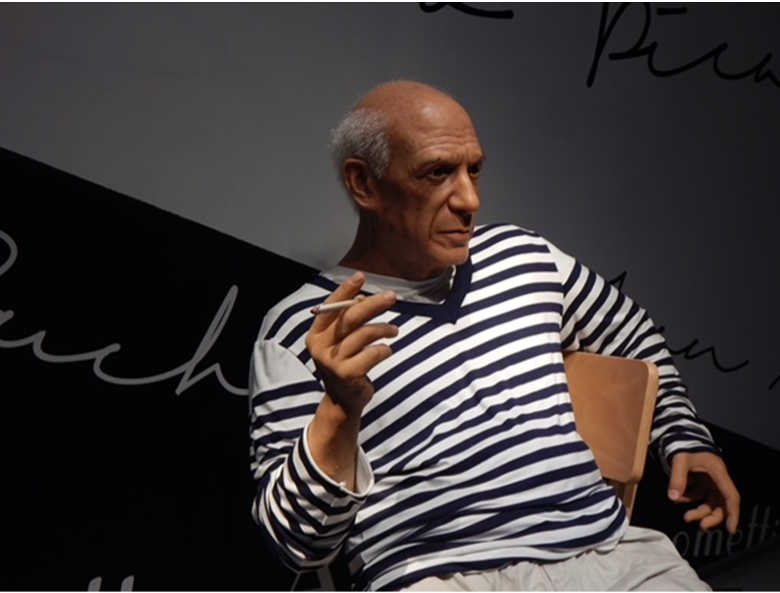

Fifty years after his death, Pablo Picasso remains one of the most prolific artists in the world, having created around 25 000 works throughout his life. It’s no wonder that I’ve seen dozens upon dozens of them at several museums since I moved to Spain last year, so much so that my response to seeing another one tends to be a mildly interested, “Oh, there’s another one.”

But the one Picasso painting that made me stop and take notice is Guernica. The first thing that struck me was its monumental size – the canvas measures around 7.6 meters in width and 3.4 meters in height. Indeed, the painting is so big that it requires two security guards on either side, ready to pounce on anyone who takes out their camera to snap a picture. (Whether photography isn’t allowed to keep the crowds moving or to preserve the painting is something I couldn’t figure out.)

Beyond its dimensions, the monochromatic palette of Guernica is a departure from Picasso’s often vibrant use of colour. This serves to emphasise the emotional intensity and gravity of the subject matter. More than that, the lack of colour allows viewers to focus on the forms, expressions, and actions within the painting, rather than being distracted by a variety of hues. Indeed, the chaotic arrangement of distorted figures—a wailing woman, a dismembered soldier, a dying horse—immediately confronts the viewer with the horrors of war.

To fully grasp the significance of Picasso’s Guernica, it’s crucial to delve into the historical backdrop against which it was conceived. The painting was created in response to the bombing of Guernica, a Basque town, by Nazi German and Italian Fascist air forces supporting Francisco Franco’s Nationalist uprising during the Spanish Civil War in 1937. This event was one of the first instances of aerial bombardment targeting civilians, marking a grim milestone in modern warfare. The tragedy deeply moved Picasso, leading him to create Guernica as a political statement and a form of protest against the brutality of war.

In the creation of Guernica, Picasso embarked on an intense artistic journey that was rigorously documented and evolved over a span of 35 days. The painting began with a linear structure that quickly took shape on the monumental canvas prepared with a specially formulated matte house paint designed to minimise gloss. As he worked, Picasso made more than thirty studies to finalise the details of the composition. (Many of these are on the walls surrounding the room in which the painting is housed, although it seems that not many people notice them.) In doing so, many elements, including key aspects like the orientation of the bull and the soldier, changed before they reached their final forms. Photographer Dora Maar played a crucial role not just in documenting the creation but also in influencing the painting’s monochromatic palette. Indeed, the generally reclusive Picasso opened his studio to influential visitors during the creation of Guernica, believing that the painting’s publicity would advance the anti-fascist cause. “The Spanish struggle is the fight of reaction against the people, against freedom,” he said at the time. “My whole life as an artist has been nothing more than a continuous struggle against reaction and the death of art. In the picture I am painting, which I shall call Guernica, I am expressing my horror of the military caste which is now plundering Spain into an ocean of misery and death.”

The painting has elicited a wide range of responses since its creation. Some critics have questioned whether the painting’s abstract and symbolic nature effectively conveys its anti-war message. They argue that the lack of a straightforward narrative or recognisable figures might dilute the painting’s political impact. On the other hand, many art historians and critics consider Guernica to be a masterpiece of anti-war art. They argue that its very abstraction serves to universalise the experience of war and suffering, making it a timeless call for peace. Nevertheless, the painting’s iconic status and its frequent display in various exhibitions worldwide attest to its enduring power and relevance.

Indeed, the journey of Picasso’s Guernica from its creation in Paris to its current residence in Madrid’s Reina Sofia Museum is a complex tale interwoven with political upheaval and public sentiment. Originally commissioned for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 International Exposition in Paris, the painting toured various cities around the world, including New York, where it was housed at the Museum of Modern Art for several years. During Franco’s dictatorship in Spain, the painting couldn’t be returned to its homeland due to the political climate. It was only in 1981, after much negotiation and public demand, that Guernica was repatriated to Spain. Finally, in 1992, it found its permanent home at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid.

Throughout its journey, the painting has been a focal point for political discourse and has elicited strong reactions from the public, making its history almost as impactful as the artwork itself. Guernica has also had a profound impact on both the art world and social activism. Over the years, it has evolved into a powerful emblem that speaks against the horrors and injustices of armed conflict. Artists across various mediums have been influenced by its striking imagery and emotional depth, often incorporating similar themes or visual elements in their own work. Likewise, activists have used Guernica as a rallying point in anti-war and human rights campaigns, underscoring its enduring relevance as a universal plea for peace. A compelling example of the painting’s influence in the political sphere is the full-size tapestry copy of Guernica that hangs at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. This tapestry, originally commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller and created by Jacqueline de la Baume Dürrbach, has been displayed at the entrance to the Security Council room since 1985. Its presence at such a significant global institution speaks volumes about the artwork’s role as a constant reminder of the consequences of war.

However, the tapestry was notably covered during press conferences in 2003 when U.S. officials were advocating for the Iraq War, sparking debates about whether its potent anti-war message was seen as too confrontational for the occasion. This incident alone highlights the enduring power of Guernica to provoke thought and challenge the status quo, even in the halls of global governance.