Faking it: The story special effects

That’s just gross…

You really can’t talk about movies without talking about special effects, and you can’t talk about special effects without talking about horror films. While snubbed by the Academy, railed against by concerned parents and grandfatherly governments, and derided by amateur and couch pop psychologists, horror often led the way for innovation and storytelling. It’s not just the powerful sense of atmosphere given by way of Gothic Horror to the world by German Impressionists during the Silent Era of film in the 1910-1920s… the use of stop motion animation by masters like Ray Harryhausen… the development of blood recipes or prosthetics… the early development of CGI and composite Visual Effects.

Many of the world’s most celebrated talent – be it acting, directing or screenwriting – started their careers in the genre. Many tastemakers dismiss horror as too gory to be taken seriously, but given the contribution to the field of filmmaking, that criticism is just a gross misstatement and underestimation of the influence of scary movies.

Dr Freud or Dr Caligari?

But the analysis holds when we consider the scary movies within the context of their own time. The Silent Era (1890s – 1920s) and Golden Age (1930s – 1949) saw most horror films centered around classic gothic tales – with fear of bloodthirsty aristocrats topping the charts.

But the analysis holds when we consider the scary movies within the context of their own time. The Silent Era (1890s – 1920s) and Golden Age (1930s – 1949) saw most horror films centered around classic gothic tales – with fear of bloodthirsty aristocrats topping the charts.

In the 1970s came the “ME ME ME” generation, and suddenly, cinemas were filled with evil children – The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby.

Social fears inform our horror regardless of how social mores attempt to control them.

The golden age Frankenstein (1931) had a line of dialogue that required censorship due to the Hays Code. After a character asks Dr Frankenstein, “What in the name of God?” he answers, “Now I know what it feels like to be God!” The second part of his answer was covered up by a lightning strike effect, made specifically to mask the words. Special effects can conceal as well as reveal. The original dialogue was only restored in 1999. However, the thunder strike effect has been used over and over, and that self-same strike can be heard in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, The Haunted Mansion, Back to the Future and Ghostbusters. Likewise, Tim Burton would not be Tim Burton without the stylised sets and production designs of the German Impressionists. Special effects can outlive their own films, and even eras, and continue for decades or even centuries after their first use. Most of the effects used in Star Wars were actually already in use when King Kong was made – and King Kong merely refined and perfected all that was already in the special effects arsenal at that point.

The House of Harryhausen

Mention the name Harryhausen to a certain generation of filmmakers, and you’ll be greeted with reverence and excitement as if you just mentioned a saint. Several big directors remember being inspired by the stop-motion monsters Harryhausen introduced to the world – and future fans of the genre subscribed to magazines inspired by the man. Special effects wizards like Tom Savini (who worked on everything from Friday the 13th to Django Unchained and spawned a whole host of VHS greats) took inspiration from Harryhausen. Harryhausen’s big contribution was combining stop-motion animation – at the time, a separate art form – with real footage. The techniques were still used as late as The Terminator and Robocop. The early work on Jurassic Park, in fact, was based on stop motion principles – until computer-generated imagery replaced it in the middle of production.

Green With Envy

Still in use whenever you watch the weather, greenscreens (which can be blue or green) essentially replace backgrounds. The actor does his or her thing in front of the canvas – and then images are either projected on the canvas or replaced in the edit suite. One of the worst examples of this was in James Bond’s car chase in Dr. No – watch it today, and it’s almost comical. Alfred Hitchcock also used the projection technique in the first half of Psycho, where the main actress drives away after committing a crime. Projection is even better and more sophisticated – the projection technique is the basis for most of the scenery in the TV series The Mandalorian. Virtual Production is changing the game, and the only certain thing with the latest tools is that you absolutely can no longer believe your eyes.

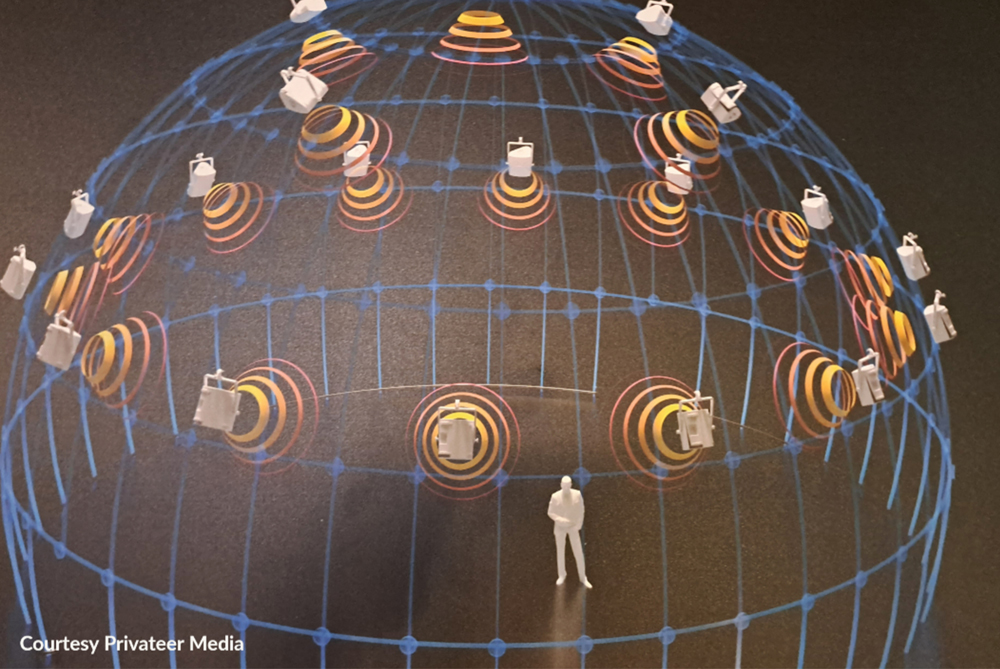

One of the latest advances is immersive filmmaking. Using the layout and techniques of a planetarium, immersive cinema's domed experiences place you within a movie rather than watching it.

Practical Prosthetics

With CGI, Compositing, Virtual Production and Immersive filmmaking all bringing the power and capabilities of technology to the forefront, it would be easy to think that all effects are high-tech. But several of the best and strongest effects are actually surprisingly low tech. Not all things can – or should – be produced by computers.

Take prosthetics. Known as “practicals”, these effects are in camera – that is – photographed as they are as part of a scene and not created in the studio afterwards.

It’s not merely as simple as casting plastic in a mould, either.

Some prosthetics are so realistic that they feel like the real thing. Little veins can be observed just beneath the ‘skin’, and they don’t feel like plastic but look and react like ‘the real thing’.

Practicals are an essential part of the horror and science fiction filmmakers’ toolbox and will never be completely replaced.

Bloody Mess

We tend to think of blood as one thing, but the truth is that modern stage blood comprises different kinds of blood to create ultrarealistic effects.

The barbed wire chain above is made of leather – it is soft and can be run over skin with absolutely no danger or pain involved. But it LOOKS pretty real, and so it is with ‘blood’.

The picture above has three different kinds of stage blood. Arterial blood – that’s the bright red – has a zesty mint flavour and is quite runny. There is also a jelly-like blood with nice bits and pieces in it for some added texture. The oldest wounds, and some of the darkest areas of the ‘bruising’ – is actually made using one of the oldest tricks in the blood book: chocolate sauce.

But this was not always the case. The Hays code forbade the showing of realistic blood. Britain’s Hammer Films – not subject to the restrictions – made a killing (pardon the pun) showcasing all kinds of blood.

In the very beginning, the red handkerchief was the perfect special effect for stage blood.

The Théâtre du Grand-Guignol, which opened in Paris in 1897 and remained a haven for those who loved gore and the macabre right up until its closing in 1962, created the first stage bloods with carmine and glycerine recipes.

Hammer Horror and others in the British film industry used what was known as Kensington Gore – a recipe developed by retired pharmacist John Tinegate – which used golden syrup as a basis.

By the time the Hays Code was abandoned and Hollywood caught up, Dick Smith laid the foundation for Hollywood’s stage blood. The problem with Smith’s blood – used in Taxi Driver, The Godfather and The Exorcist, among others, was that one of its primary ingredients, Kodak Photo-Flo, was very, very toxic.

Today, the market is spoiled for choice, with all kinds of stage blood available for purchase.

However, in a pinch, some corn syrup and food colorant will more than do. Two drops red, one drop blue, maybe half a drop of green, and stir….

Everything about the movies is based on illusion. Scary movies bring us the best illusions by ultimately showing us that what we fear most are themselves illusions.